The Writing University conducts is a series of interviews (the "5Q Interviews": five questions to all) with writers while they are in Iowa City participating in the International Writing Program's fall residency. We sit down with authors to ask about their work, their process and their descriptions of home.

Today we are talking with Dilman Dila, a fiction writer and filmmaker from Uganda.

1. Do you have a plan or project in mind for your time at the residency?

Yes. I'll use my time at Iowa to rewrite and refine a novel, tentatively called Ja'kewana. I started writing it earlier this year, in the military sci-fi genre, and it is autobiographical with fears from my childhood. I have a disability, club-foot or polio, not sure what it is exactly. Growing up in the '80s, my country was in a fragile place. War could break out anytime and I feared when it did I would fail to run fast to safety. Other children teased me, saying, “We shall run and leave you behind.” Today, each time I see news about conflict and refugees, I wonder how those with disabilities get out, if they ever get out. I think this thing bothered me for all these years, seething somewhere in my subconscious, for when I started to write the book, 120,000 words spewed out in about three months, though in that time I traveled to two festivals and had a lot of work distracting me. I tentatively call the book Ja'kewana and when I sent the first few chapters to a publisher, Guardbridge Books, they picked interest in it and are keen in bringing it to life. We hope to put it out later this year, or early next, so the residency at Iowa comes as a blessing, for I'll have time to focus on finishing the novel without distractions.

2. What does your daily practice look like for your writing? Do you have a certain time when you write? Any specific routine?

No, I don't have any specific times or routines for writing. I treat it like a job, and set myself targets for each day. It does not matter where or when I start on the target, as long as I achieve it by the end of the day.

3. What are you currently reading right now? Are you reading for research or pleasure?

I'm reading Octavia Butler's Lilith's Brood. I love her work. The first book of hers that I read, Wild Seed, encouraged me to write science fiction with protagonists of color. Before that, I could not imagine a black protagonist in a scifi novel, and when I picked the book, I didn't even know who she was. I thought she was a man. I tried reading the biography at the back of the book, for I wanted to know if the writer was a person of color, but the biography said very little, and I assumed she was a man, until many years later. Still, her name, and her writing, stuck, and so whenever I come upon any book of hers, I read it. I read for pleasure, I never read for research or for work, and if I do, then it is always a short thing I can finish in a few hours. If I start reading for research or for work, it would become such a chore that I would lose all love for it.

4. What is something the readers and writers of Iowa City should know about you and your work?

I'm not sure of what people should know about me. I always try to keep in the background, to under-impress on first encounter, and I always hope my works speak a lot about me, for much of my writing borrows heavily from my own life experiences. It's easier to write about my experiences in the speculative fiction genre, especially dark stories of the scifi/horror kind, than if I were writing in the literary genre, for spec-fic gives me a broader field to play with. I always think of myself as some kind of social activist, for I'm aware that stories have the power to change people, any story can influence how anyone thinks. I however avoid preaching and messages, and instead focus on the circumstances a character is going through, and I hope a reader (or viewer in case of films) will learn something from how the character deals with their problems. It's easier to write effective stories that can inspire an audience if the characters are going through something I experienced.

I think I also write to deal with the trauma of living – you know life is hell, and some people, like me, only see the hottest part of it. So when I write, I try to look for a piece of heaven. Like earlier this year, I ran broke, so broke, all of a sudden, and I did not expect to see any money for another month. In that time, I had to stay mostly indoors. You don't spend much if you keep indoors, but you can't get rid of the stress of not having money. So I started to write, the novel I mentioned earlier, Ja'kewana, and it distracted me from money issues. Time passed faster than usual. The money came before I could really feel the pain of being broke. I don't look at it as escapism, nor do I try to re-imagine my life in another world, I mostly look at it as a tool of healing, the way someone would go to a therapist when they are depressed, or to a doctor when their hand is broken.

5. Tell us a bit about where you are from -- what are some favorite details you would like to share about your home?

I grew up in a small town that has the characteristics of a very large city, it was kind of a melting pot of cultures. Most towns of Uganda are predominated by one ethnic group, but Tororo, though based on land that belongs to the Jo'Padhola, was in colonial times incorporated into a district with several ethnic groups. Being also the entry point of the railway from Mombasa into Uganda, it attracted a lot of Asian business people and was a major administrative place. In the beginning there was an apartheid system, the whites lived in a suburb called Senior Quarters, the Asians in the center of town, where they ran all the businesses, and Africans in other, poorer, suburbs and slums. After independence, affluent Africans moved into Senior Quarters and then after Amin expelled Asians in 1972 the politically connected took over the businesses. By then, the town did not belong to any particular ethnic group, and the main language in the streets was, and still is, Kiswahili. It is the first constituency in post-Independence Uganda to elect an Asian to parliament. Often, this characteristic of my home town seeps into the worlds I create.

Tororo is in the Eastern part of the country, my father comes from the Western parts, and my mother from the Northern parts. So I grew up in a town not connected to either of my parent's ancestry, and since this town was a cultural melting point, I sometimes feel culturally lost. What in Kiswahili is sometimes called 'kosa kabila', which loosely translates to 'those without a language/ethnic group/tribe'. When I was younger, other children would insult me; “You are lost. You don't know where you come from.” Today, my accent is vague, and it is easy for me to learn new languages, and to pick up new cultures. I discovered this was true when I went to Nepal in 2009, and learned Nepali in three months, and fit in so well that the only thing that distinguished me from Nepali, and caused me a lot of grief, was that I was a tall, very dark African man. In Uganda, having grown up in Tororo still haunts me, for when I say Tororo is my place of birth, and my hometown, those who have not grown up in it ask; “So you are a Ja'padhola?” And when I say “No,” they get even more confused. No one expects someone to grow up in a small town and not belong to the ethnic group associated with it.

Tororo, Uganda

Tororo, Uganda

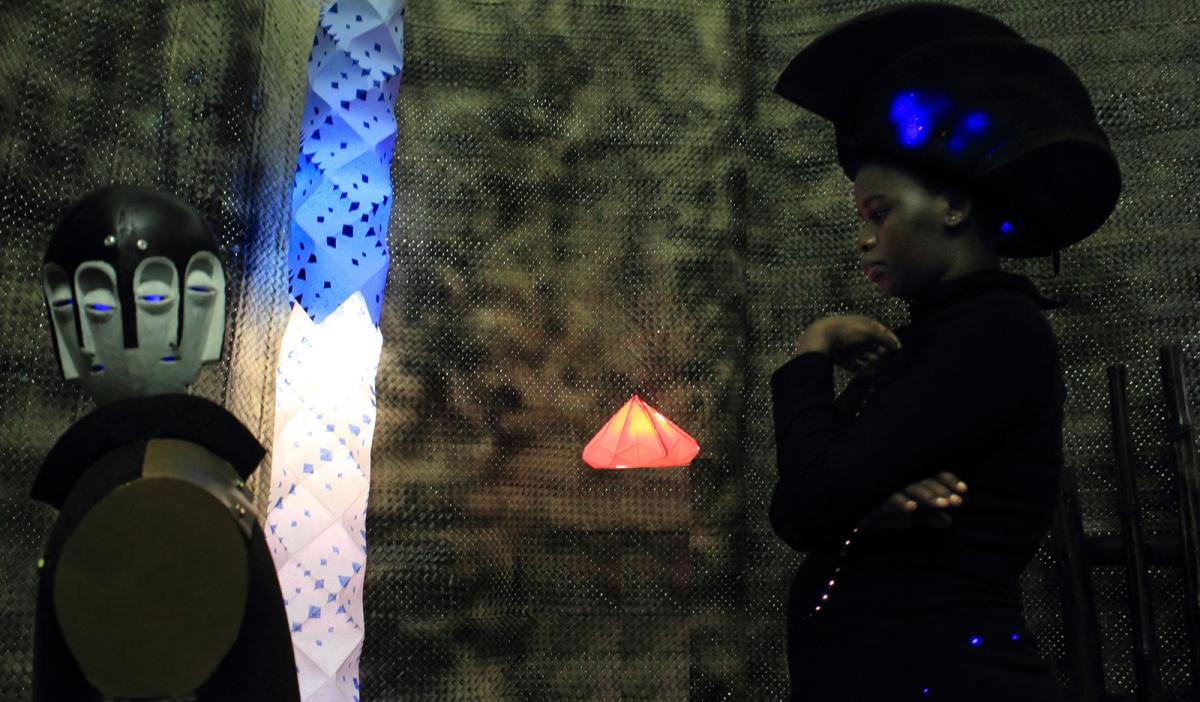

Still from "Her Broken Shadow"

Still from "Her Broken Shadow"

**

Thank you so much, Dilman!

Check the IWP website for events that will include Dilman Dila throughout the residency.